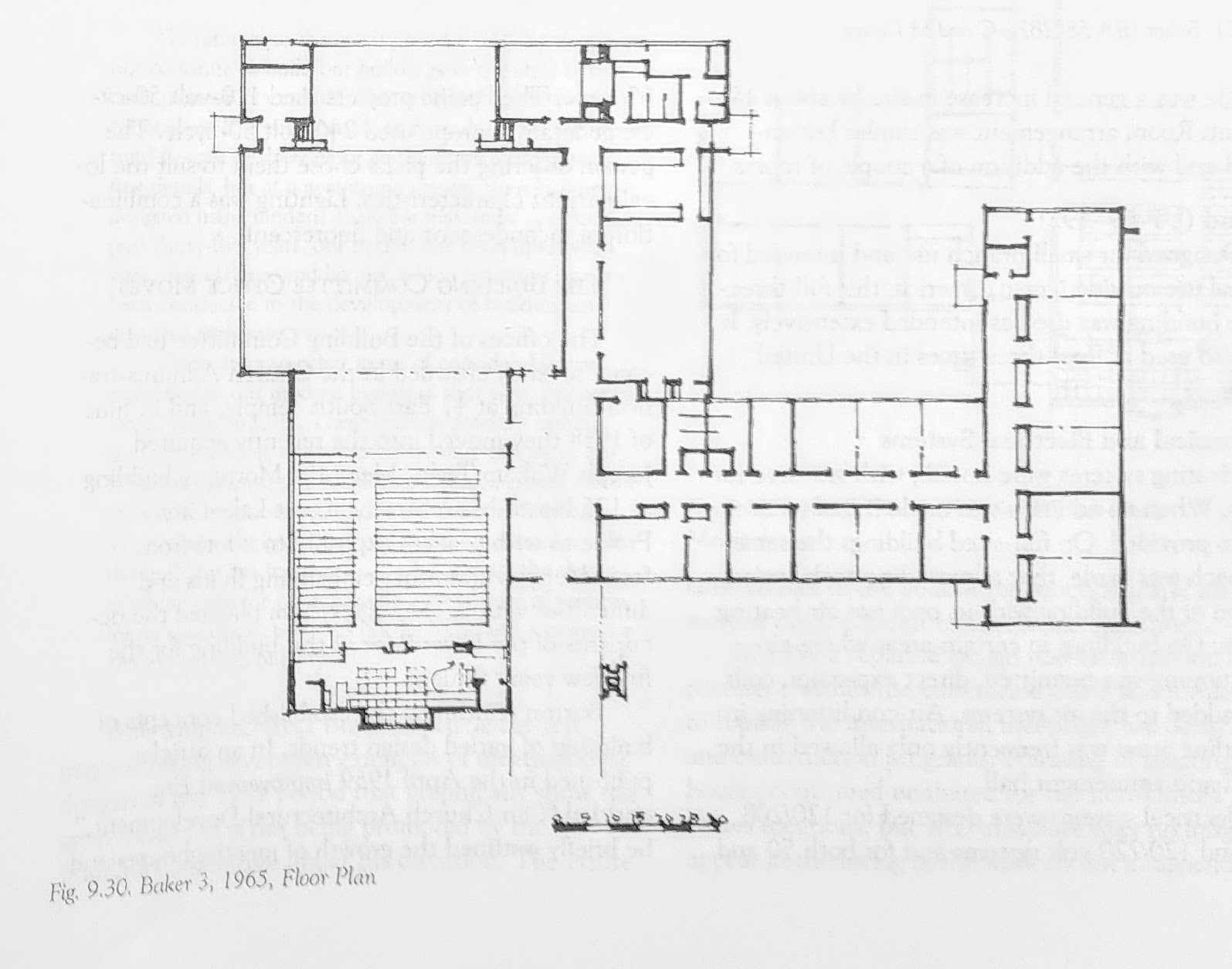

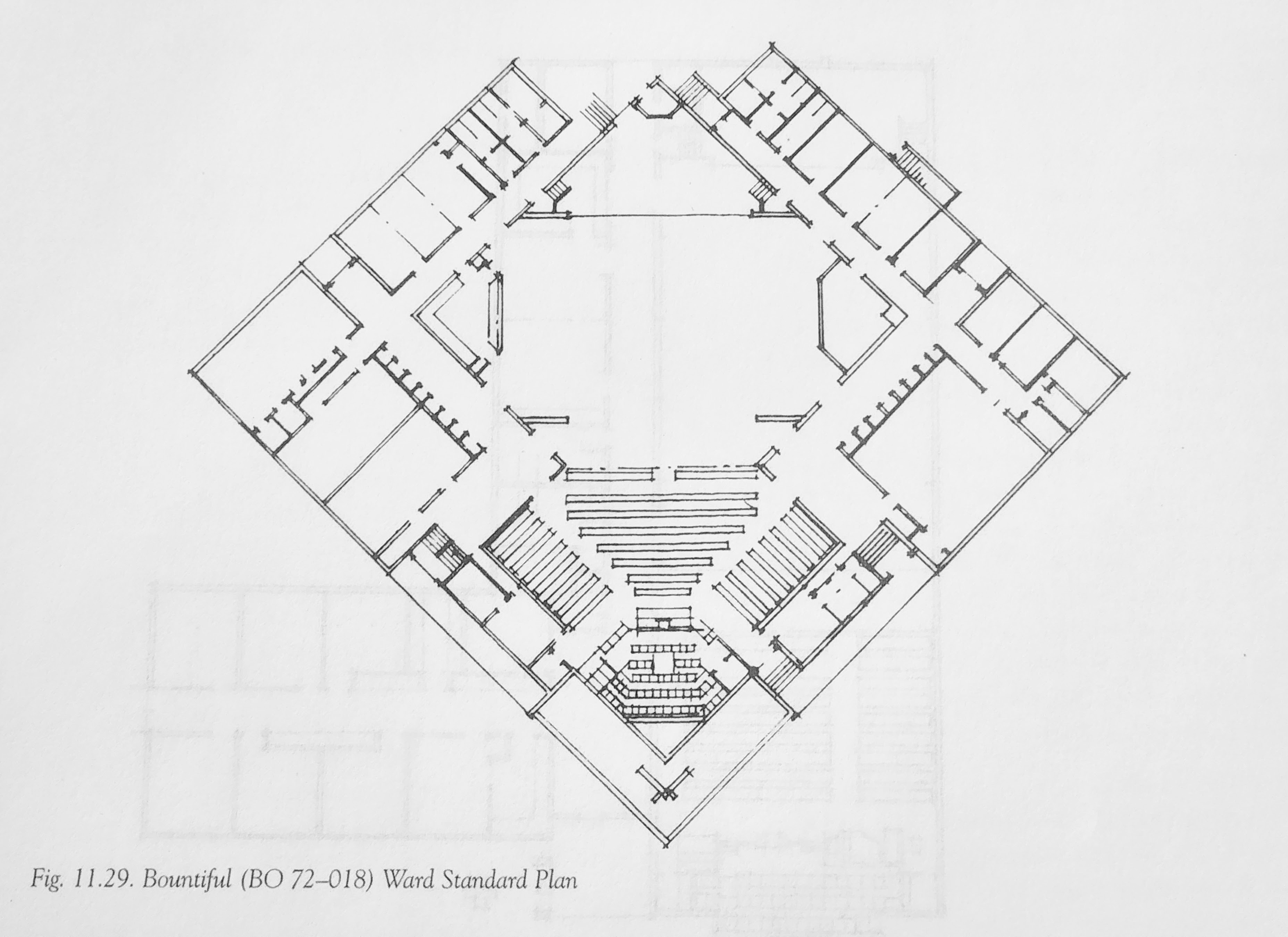

The modern period of LDS architecture (1958-1977) represented a complete rejection of the classical architectural tradition. Gone were the arches, pilasters, and columns that had adorned churches for generations. A pure and disciplined modernism reigned supreme. However, in 1977 and 79, the church introduced two new standard plans that marked the end of the modern period and pointed LDS architecture in a new direction, one that would soon return to the classical tradition.

The Brower and Cody Standard Plans (1977-79)

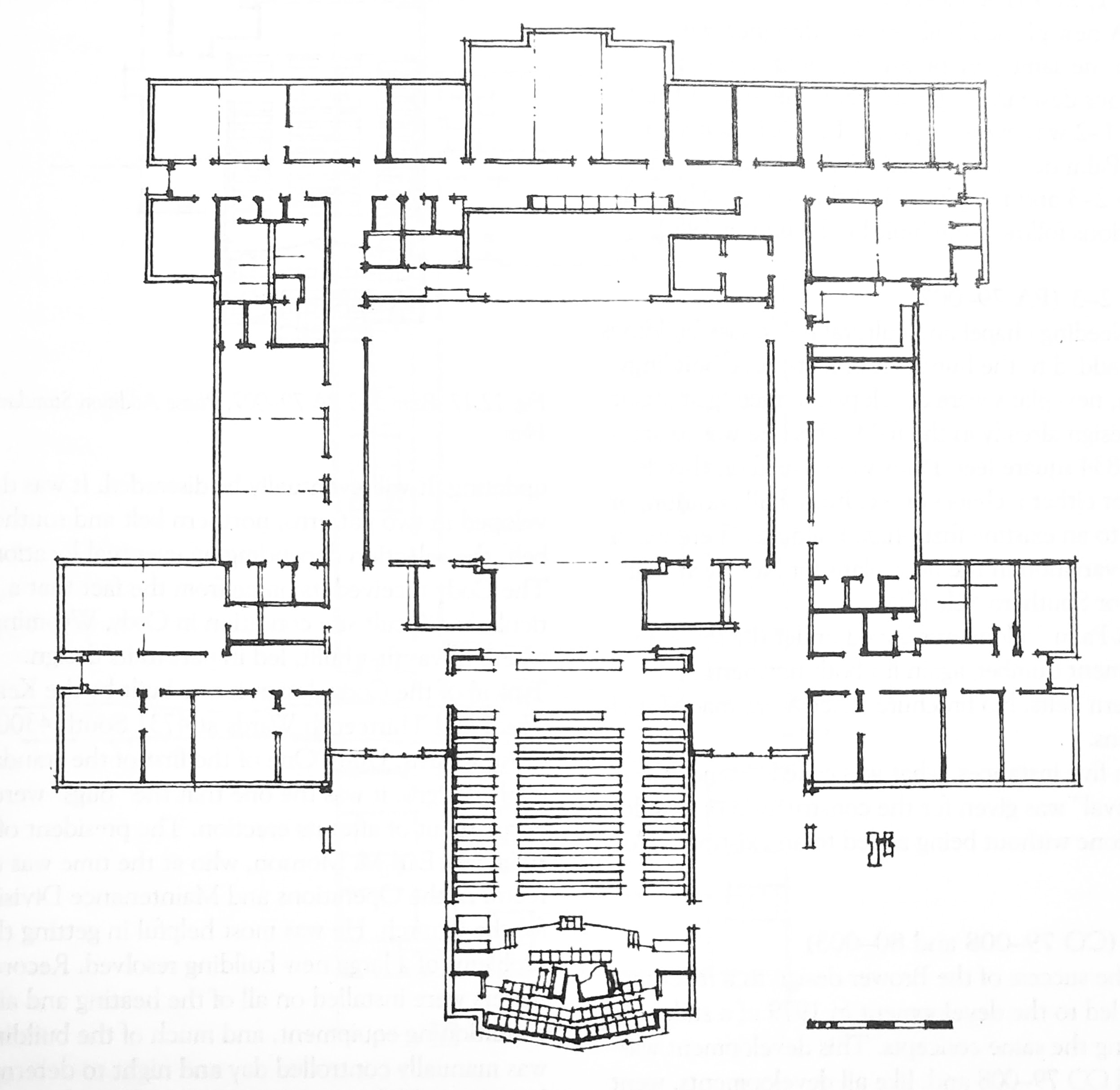

It is hard to overstate the influence that the Brower and Cody standard plans had on LDS meetinghouse architecture. Their overall format is very similar to the format of most meetinghouses built today. Richard L. Jackson’s survey of LDS architecture Places of Worship had this to say about the introduction of the 1977 Brower Standard Plan: “The building became an experimental model and was monitored closely for function, heating, ventilating, air-conditioning, and electrical parts. The results of this monitoring were incorporated in subsequent designs. The success of this Brower plan was such that a short moratorium was called on new ward meetinghouses in order that the Brower could be used instead of the earlier standard plans.”

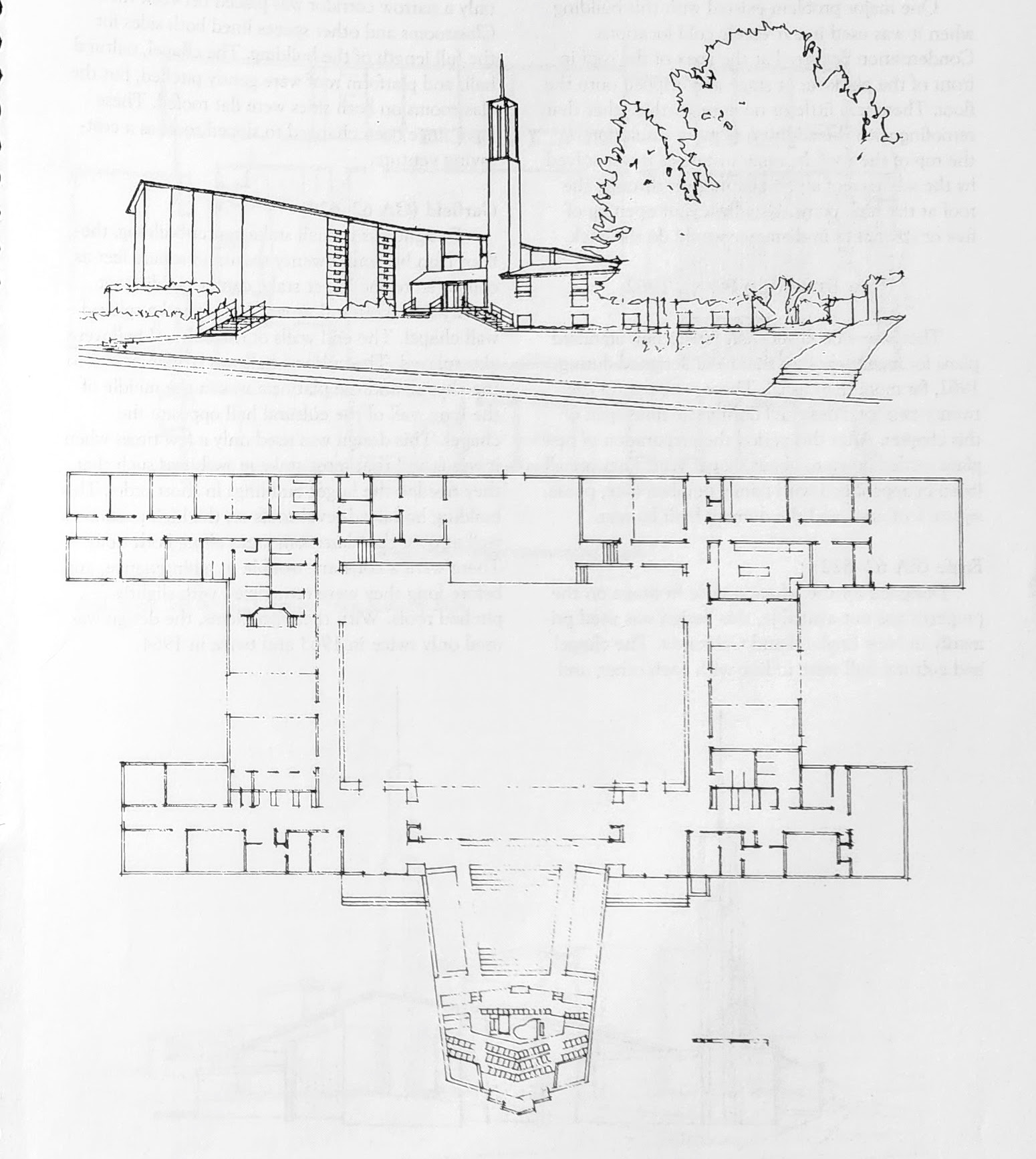

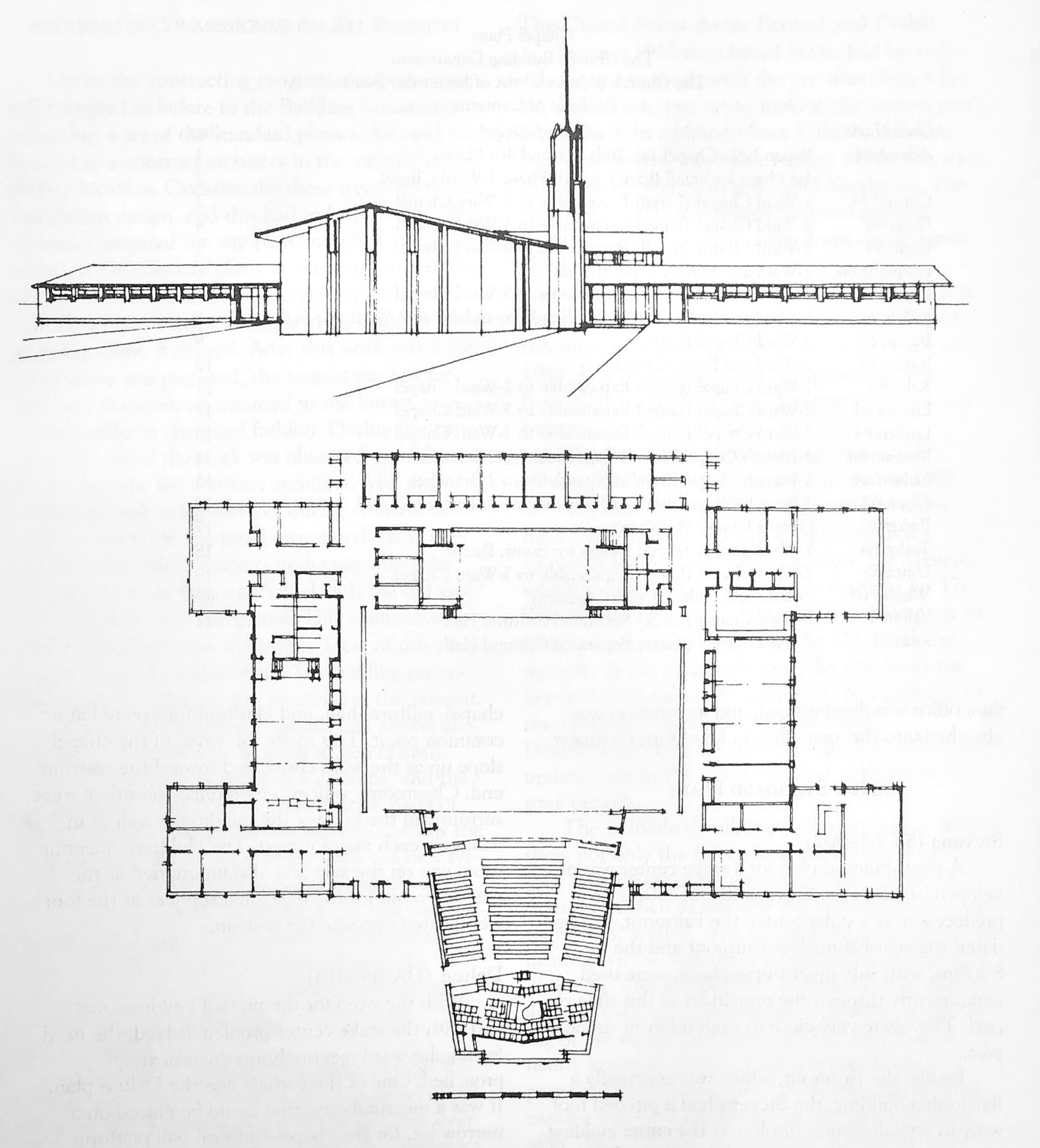

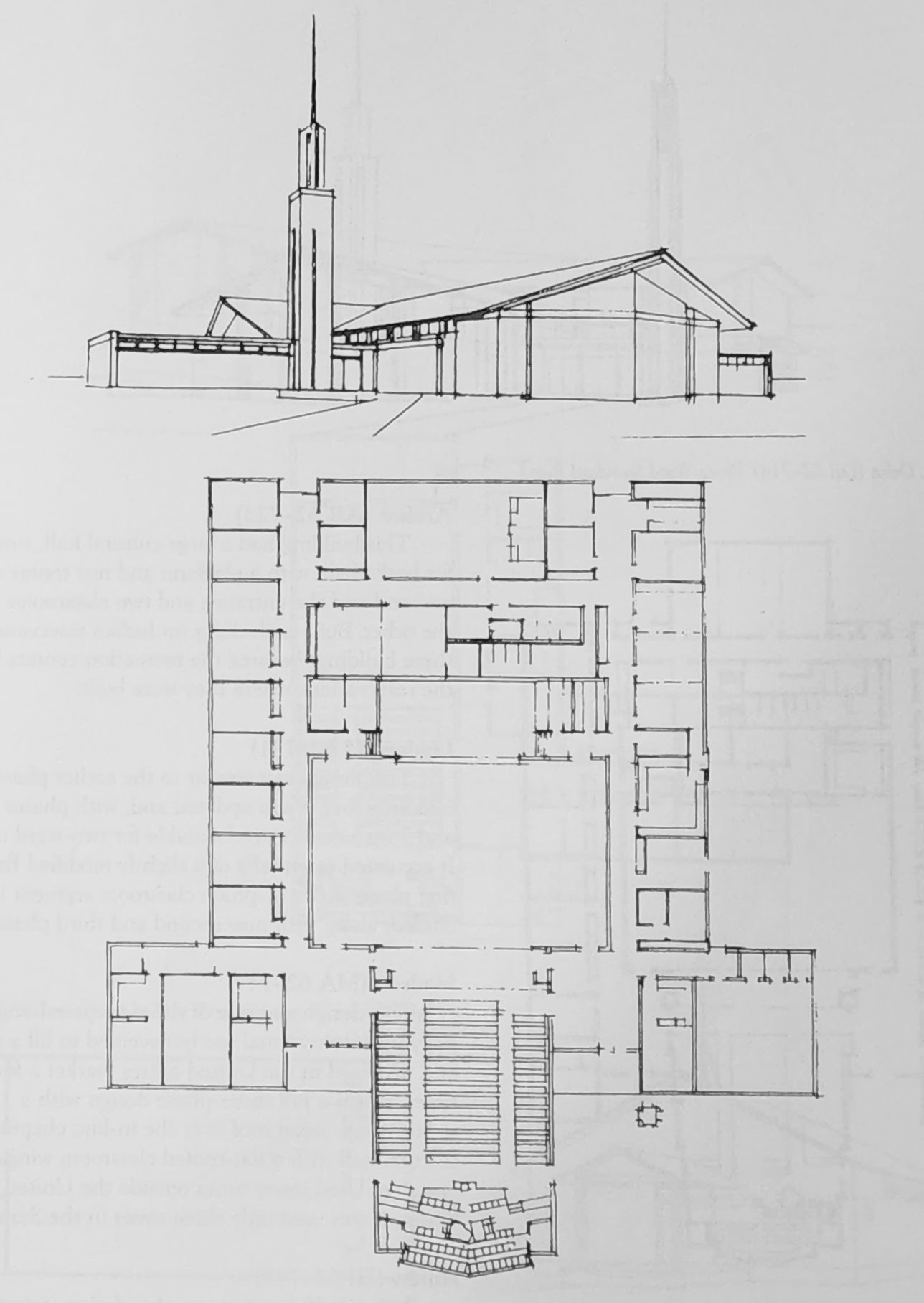

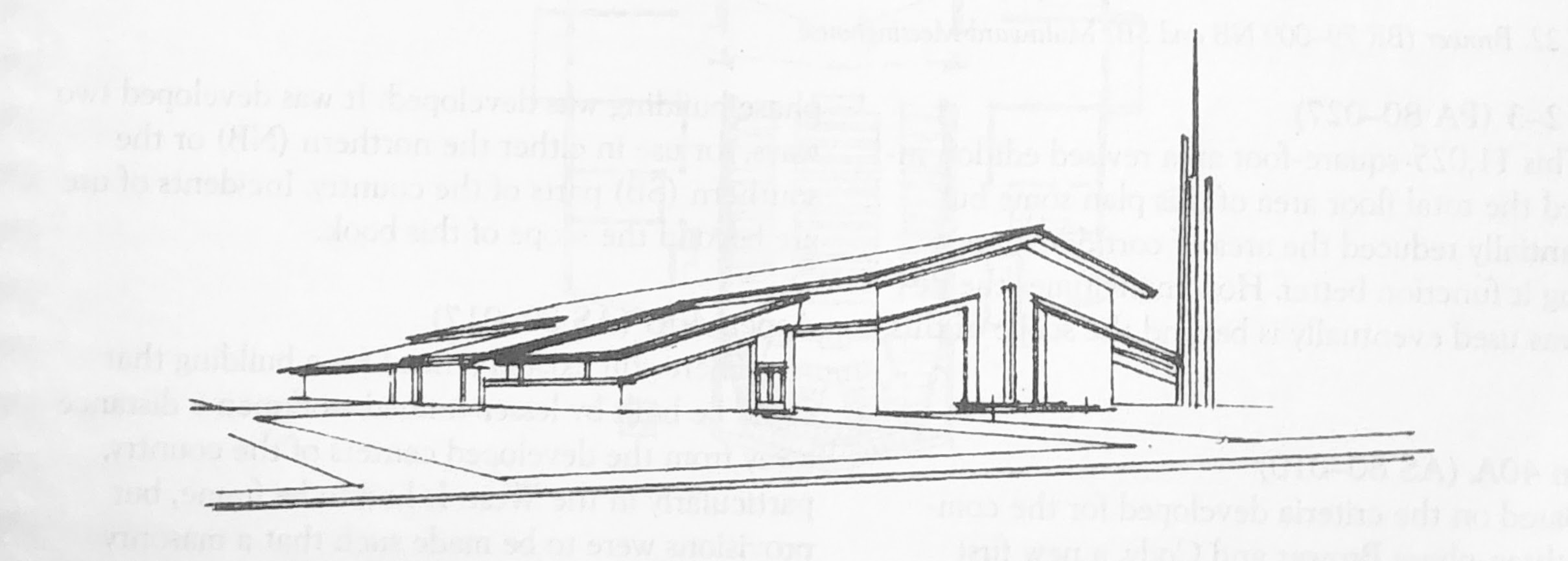

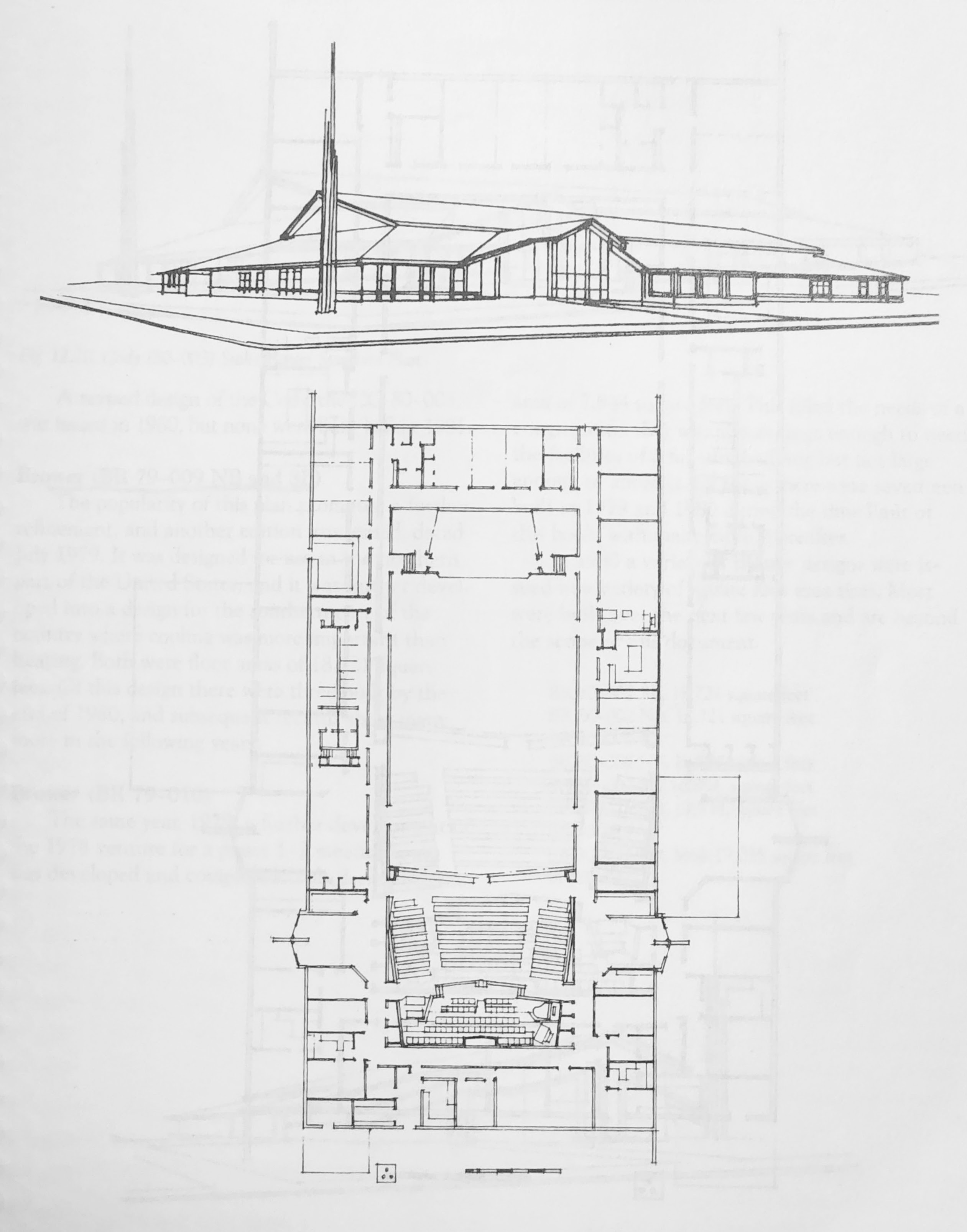

The Brower plan placed the entire meetinghouse under a single gabled roof structure which greatly increased the affordibility and efficiency of the building. The Cody plan (first built in Cody, WY in 1979) economized even further by eliminating the facade of the meetinghouse entirely and replacing it with a hipped roof which descended to a first floor bank of windows (see illustration above).

The End of Modernism

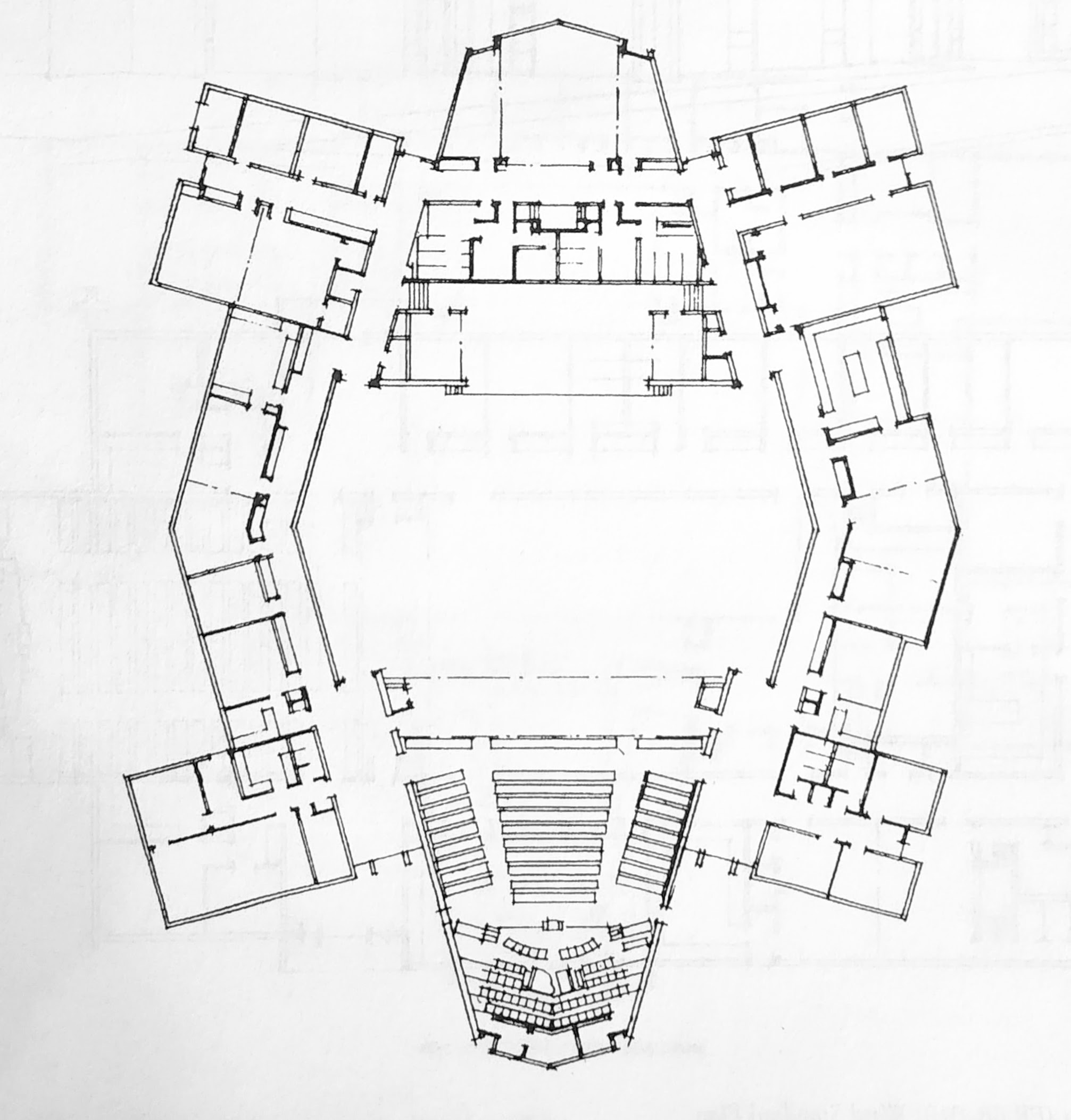

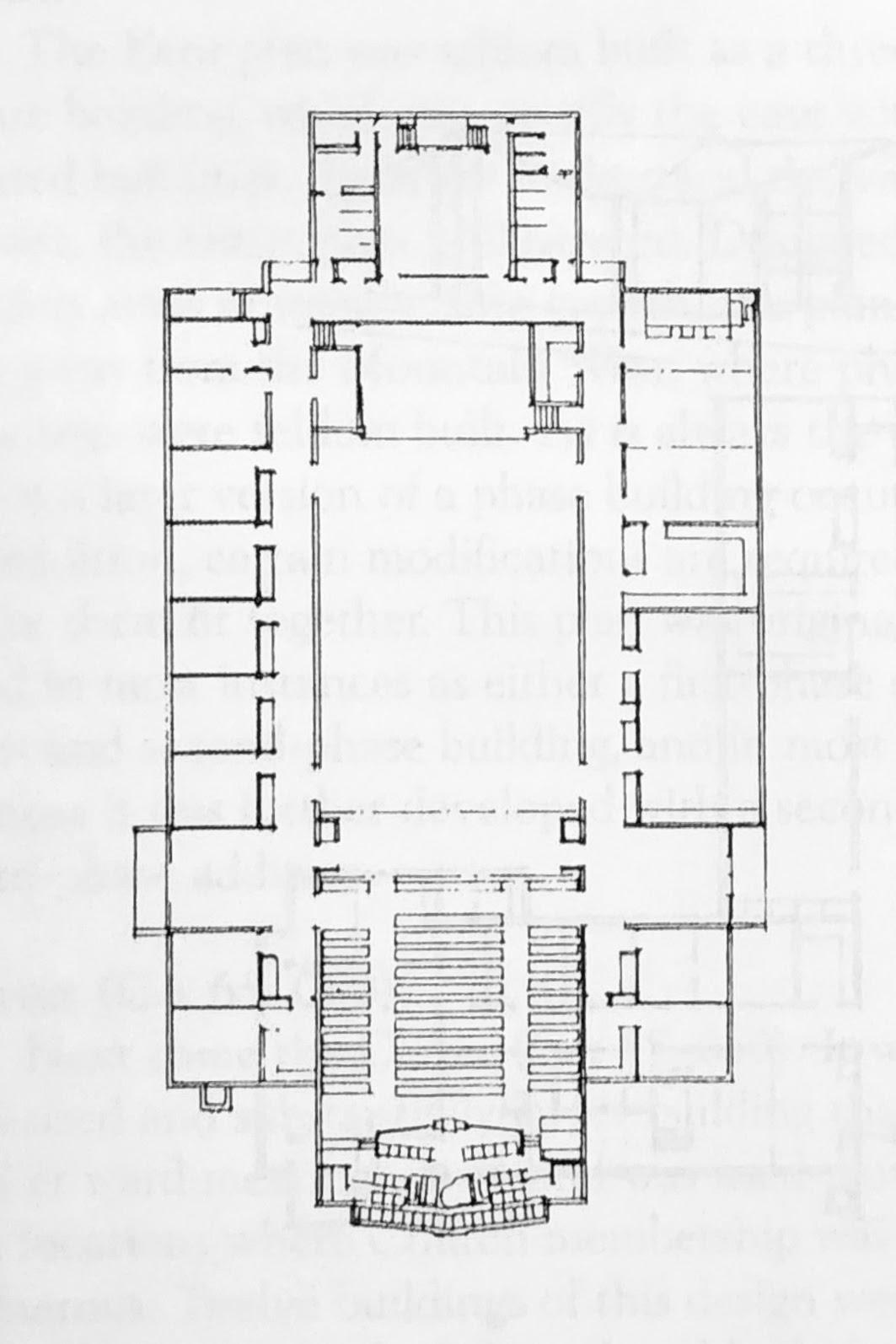

What the Brower and Cody plans gained in efficiency, they sacrificed in silhouette. The modernist motto “form follows function” dictates that a building’s function should be apparent in its form. During the 60s and 70s one could always tell from the outside that an LDS meetinghouse consisted of a central chapel surrounded by shorter wings for classrooms and offices. It was a pleasing combination of abstract forms: squares, gables, and rectangles, punctuated by a modern spire. The form of these buildings matched their function. However, in the new Brower and Cody standard plans, it was not obvious from the form of the building what the function was. The Cody was particularly problematic because the chapel facade was missing entirely. What kind of building was it supposed to be?

In the Brower plan, the facade was retained. However, it was decorated with a stylized, post-modern design devoid of any apparent religious or architectural value. Again, the question could be asked, is this actually a house of worship? How could a careful and conservative church have approved such a design? A possible answer to this question can be found in examining architectural trends in the 70s and 80s more broadly. The 70s were a traumatic decade, both for American society, and for architecture in general. Post-modernism was the response, with its sometimes playful, sometimes cynical mixture of old and new ideas. During this period the LDS church was also experiencing explosive growth and needed to find more economic ways of serving its growing membership. In the midst of this social and religious transformation, the modernist architectural vision had been lost.

The interior of the Brower and Cody plans also departed dramatically from the other standard plans. Previous chapel interiors had an “enclosed” feel about them. They often featured organic materials like brick and darkly stained wood paneling, which gave the enclosure a warm, comforting quality. The Brower and Cody chapels have the opposite effect. They are broad, open, and filled with light. The cove lighting surrounding the chapel is set lower than in the other standard plans, which makes the ceiling feel open and expansive. Additionally, the ceiling has a sculptural quality reminiscent of abstracted clouds, enhancing its sky-like qualities. Long courses of wood paneling emphasize horizontal rather than vertical lines. The Brower and Cody standard plans would change the nature of LDS chapel design going forward. To this day, LDS chapels all have a wide, bright, and open feel to them.

The Return to Traditionalism

It didn’t take long before architects started decorating the Brower and Cody plans with classical and colonial motifs. The utilitarian rain gutters were redesigned with long courses of aluminum dentils. Porticos with columns were added to side entrances. Arched windows were also added. The steeple was replaced with an ornate, colonial style bell-tower, complete with a balustrade. This was a radical departure from the modernist period of the 60s and 70s. It may have been precipitated by social changes in the United States during the late 70s which saw the emergence of a new, consolidated conservative movement which idealized America’s founding fathers and colonial religions they belonged to.

However, it is also possible that LDS architects saw traditionalism as a way to solve the aesthetic problems that the Brower and Cody models created due to the rejection of the modernist silhouette. Their consolidated, rectangular design could be reimagined in two traditional ways: as a cruciform design reminiscent of a cathedral, or as an expanded version of the colonial American church house.

A Cruciform “Cathedral”

The Brower and Cody plans were rectangular structures with two gabled entrances on their sides. These entrances could be expanded upward and outward to create a cruciform structure reminiscent of a small medieval cathedral. LDS architects sometimes highlighted the medieval connection by decorating these entrances with round windows reminiscent of the rose windows of French gothic cathedrals. A gothic version of this cruciform structure was built near Park City (shown above).

An Expanded Colonial Church House

Ultimately, the most successful revision of the Brower model was its reconfiguration to resemble a colonial American church house. Historically, colonial churches featured a classical facade topped by an ornate bell tower. This sometimes made the churches look “top-heavy.” Classical facades were designed for ancient Greek temples with no steeples or bell towers. Church architects in the colonial period like Charles Bulfinch had to go to great lengths to mitigate the problems that arose from adding bell towers, for example, by adding large porticos to the facades to create a more pleasing sense of proportion.

LDS architects stumbled on a unique solution to this old architectural problem. The Brower model had a wide gabled roof that descended from the two-story apex down to the first story roofline. This meant that the entire structure was grounded, well balanced, and easily able to support a bell tower without looking top-heavy. The result was a masterpiece of proportionality. To get a sense of just how perfectly the design works, imagine the circle of the Mercedes Benz logo superimposed on the image below. You can see how the structure divides the circle into perfect thirds.

Classical Interiors

With the exterior changes to the Brower and Cody models, modernist elements in the chapel were stripped away and replaced with classical motifs. The bright, open aesthetic was retained and in some cases enhanced with lighter wood stains, brighter lights, and soft pastel coloring. The result was a new kind of chapel experience, one that felt particularly welcoming, bright, and comfortable. This sense of comfort is enhanced by the traditionalism that is associated with classical architectural motifs.

A Modernist Revival?

The Brower and Cody models marked the beginning of a triumphant return to traditional architectural forms in the LDS church. Their influence has never been surpassed and is likely to endure for some time to come. However, it is also worth considering what was lost when Brower and Cody took over, particularly the beautiful modernist silhouettes of the chapels from the 60s and 70s. I’ve noted elsewhere, the new chapel built in downtown Salt Lake City in 2022. Could this point towards a modernist revival in the future?